PAST PROGRAM

UNSEEN:

Women’s Art Register members’ exhibition

11—27 July 2025

Australian Catholic University Gallery

St Patrick's Campus

26 Brunswick Street, Fitzroy

OPENING NIGHT

Friday 11 July, 6–8pm

UNSEEN showcased a collection of artworks by Women’s Art Register members. Each artist personally selected a piece that has received little or no exposure, offering a rare glimpse into hidden creative narratives. The works were created across different time periods and in a diverse range of mediums, spanning painting, sculpture, photography, textile art and more.

By bringing these unseen works into the public view, the exhibition challenged the historical underrepresentation of women in the visual arts and highlighted the importance of visibility, recognition and artistic agency.

The exhibition room sheet and catalogue, designed by Brianna Simonsen, can be downloaded below.

Curated by Annabell Lee, Brianna Simonsen and Kate Smith.

Exhibitors: Carmel Wallace, Sharon Bush, Lea Kannar-Lichtenberger, Beatrice Magalotti, Claudia Pharès, Dans Bain, Denise Keele-bedford, Carolyn Cardinet, Laurel McKenzie, Michelle Harrington, Charlene Walker, Polly Hollyoak, Jennifer Goodman, Jasminka Ward-Matievic, Mel Jane Wilson, Regina McDonald, Kirsty Gorter, Charlotte Clemens, Carmel O’Connor, Nicole Kemp, Robyn Pridham, Alex Bridge, Hunter Smith, Veronica Caven Aldous, Ali Griffin, Gail Stiffe, Linda Judge, Tracey Lamb, Pamela Kleemann-Passi, Irene Holub, Linda Studena, Kylie Fogarty, Wendy Kelly, Tania Lou Smith, Fiorella Fabian, Katie Stackhouse, Kristen Flynn, Luci Callipari-Marcuzzo, Rosalind Simonsen, Louise Saxton, Tai Snaith, Brigit Heller.Download Room Sheet [PDF, 135KB]

Download Catalogue [PDF, 327KB]

Michelle Harrington, Doughnut Barbie (2023), Sculptural painting; found objects, ceramic, electronic, craft objects, combined 27 x 33 x 7 cm

Mel Jane Wilson, Keyhole: Echoes of Christian’s Windows (2025), Watercolour and pencil on cotton rag 650gsm, 37 x 25.5 cm

Louise Saxton, Untitled (2013), Reclaimed needlework, lace-pins, milliners straw, 29 x 28.5 cm

Carolyn Cardinet, Never Shown (2012), Found plastic, 19 x 12 x 16 cm

Veronica Caven Aldous, Rear window (2023), Photograph of programmed LED light installation, 30 x 39 x 3 cm

Carmel O’Connor, MIDWINTER (2004), Oil on linen, 25 x 30 x 2 cm

Nicole Kemp, Eternal Vigilance (2021), Textile sculpture, easter egg wrappers, scrap fabrics, machine and hand stitch, 17 x 12 x 20 cm

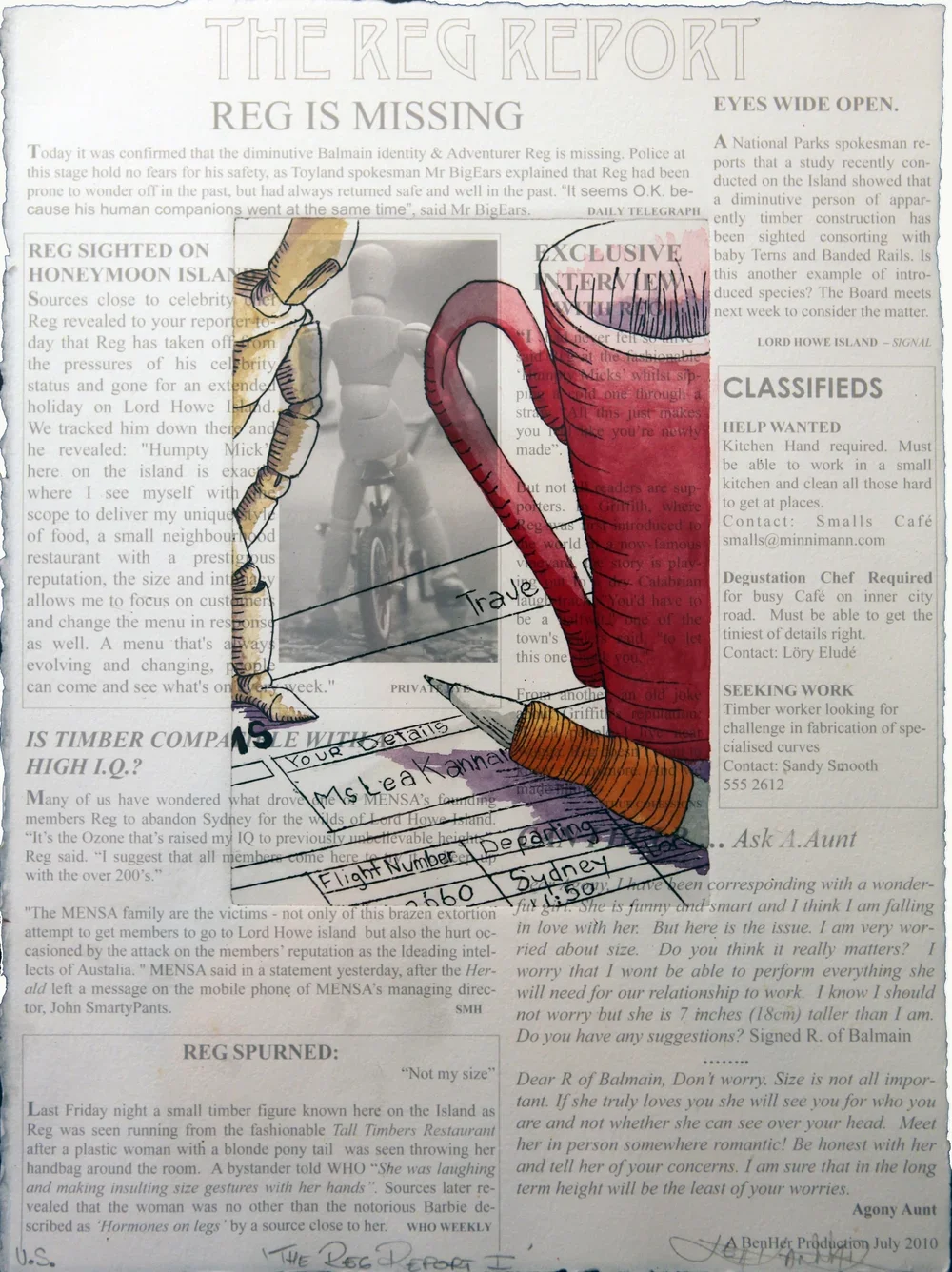

Lea Kannar-Lichtenberger, The REG Report (2010), Hand coloured, aluminium etching (A holiday on Lord Howe) and digital print on BFK, 31 x 51 cm

Denise Keele-bedford, Preciousness (1998), Mixed media, 40 x 30 x 20 cm

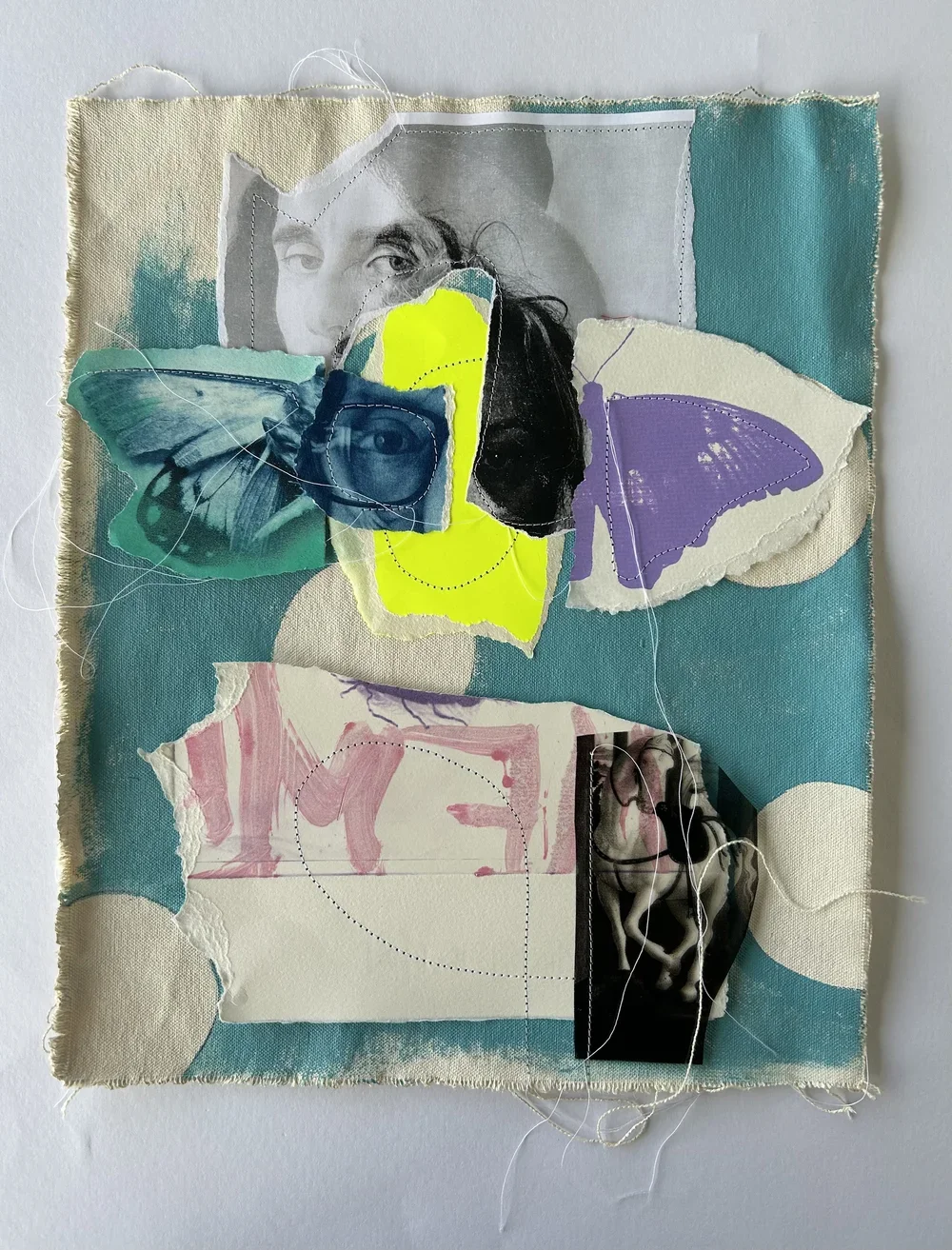

Kristen Flynn, Self-portrait butterfly head with Botticelli man and horse (2025), Mixed print media on canvas, 30 x 37 cm

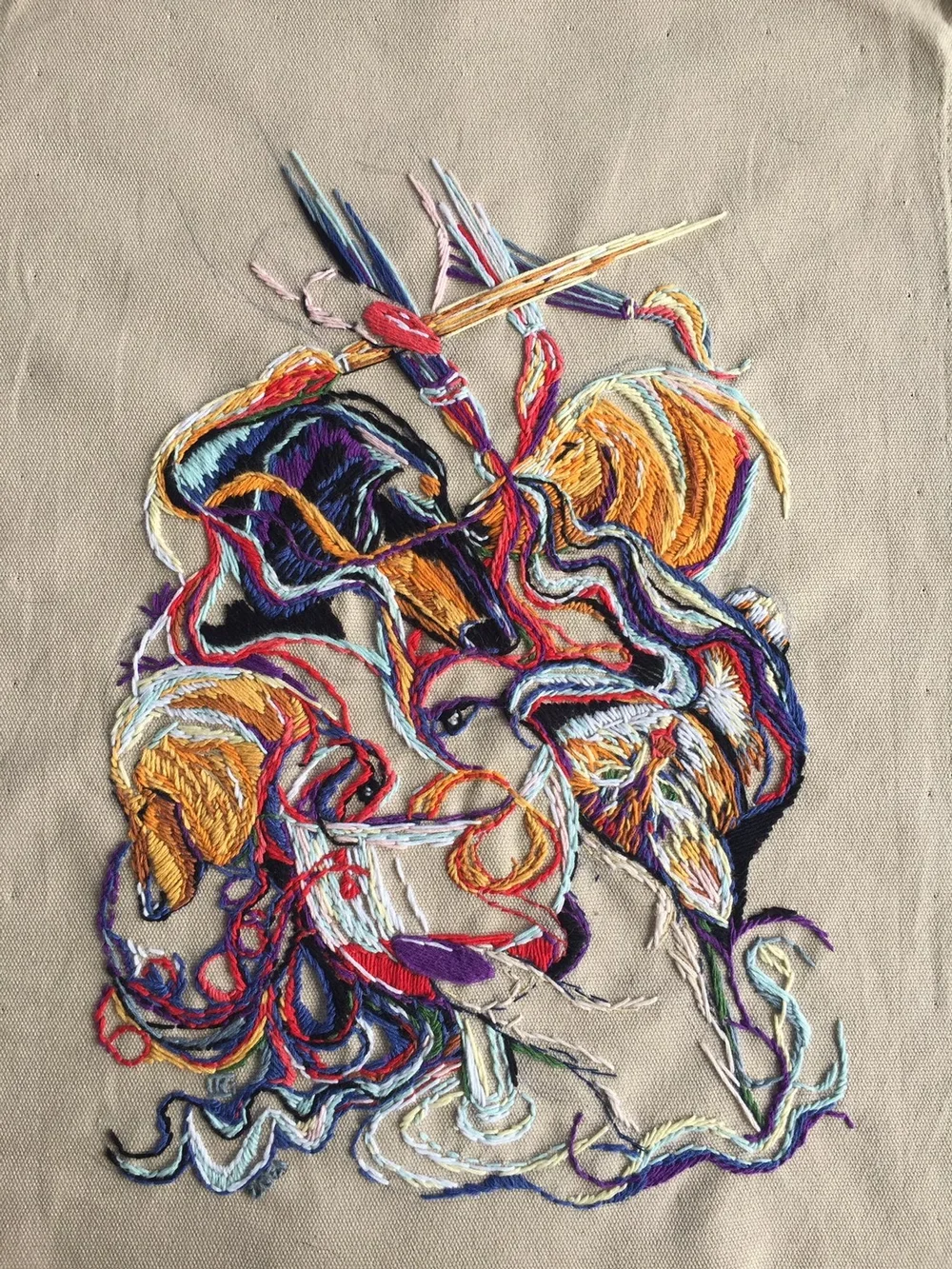

Kirsty Gorter, Isolating with Familiars (2021), Free form long stitch, cotton thread on linen, 28 x 40 cm

Tai Snaith, Ambiguous Etymology (study of inside my eyelids after crying) (2023), Gouache on paper, 40 x 30 cm

Gail Stiffe, Korea Journal (2004), Handmade paper artist book, 32 x 27 x 13 cm

Sharon Bush, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) (1988), Hand crafted painted porcelain necklace, 22 x 15 cm

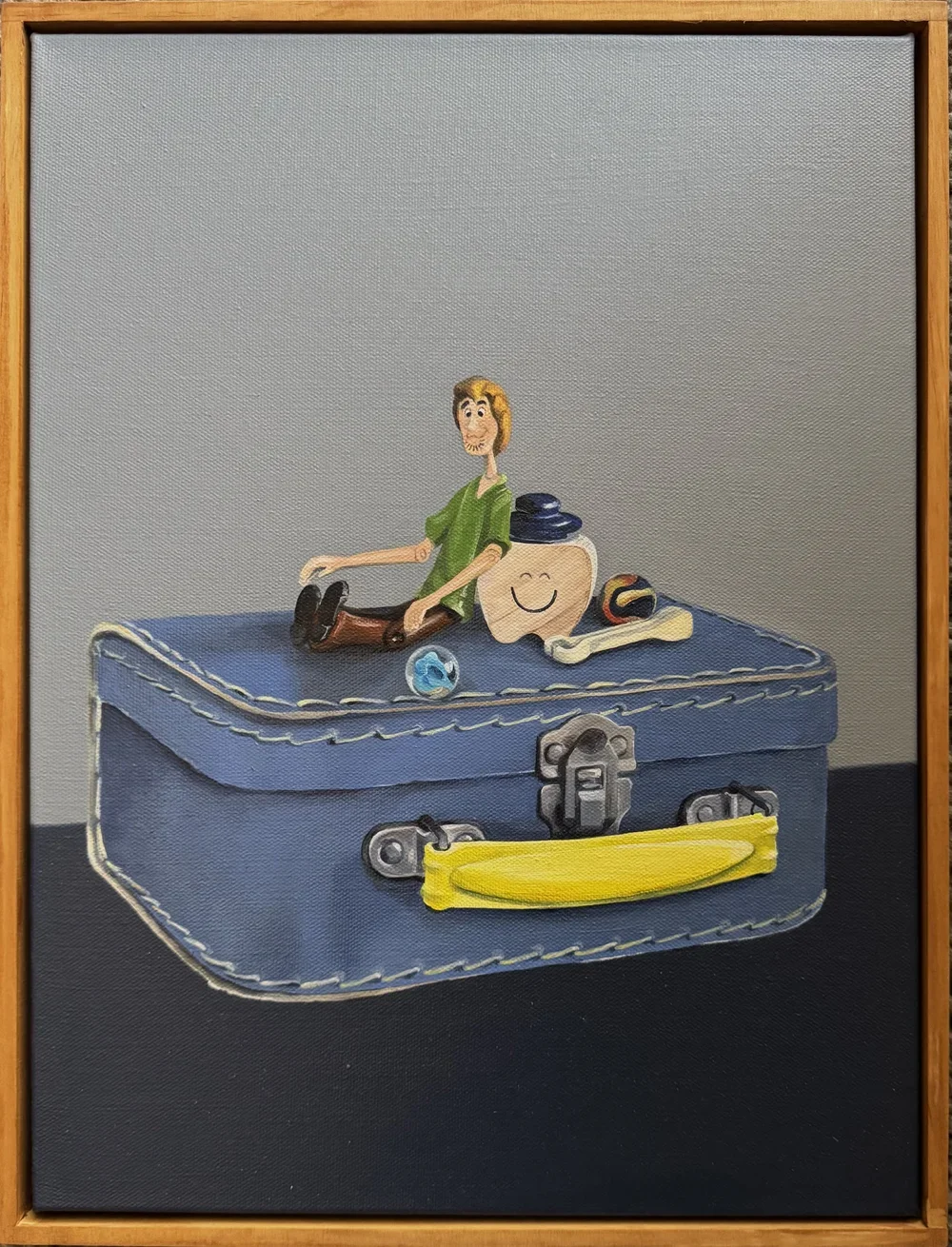

Polly Hollyoak, The Little Things (2024), Oil on canvas, 40 X 30 x 3.5 cm

Alex Bridge, Amarilla (2017), Acrylic on stretched canvas, framed 28 x 33 x 3 cm

Irene Holub, Lost in Translation (2022), Photography, 29 x 40 cm

Robyn Pridham, Friday 23rd October, 2020 (2020), Collage and mixed media over a print, 38 x 30 cm

Laurel McKenzie, Hatshepsut i (2012), Acrylic paint, buttons, beads on stretched canvas, framed 30 x 30 x 5.5 cm

Tracey Lamb, la chaise de la dame (2017), Aluminium and timber, 14 x 11 x 16.5 cm

Dans Bain, Vestige (2012), Textile, 40 x 30 x 40 cm

Jasminka Ward-Matievic, Maria Likarz-Strauss (2015), Reworked digital reproduction on cotton (wool, cotton, beads, repurposed materials), 38 x 30 x 4 cm

Claudia Pharès, Home Works (2020), Photography, 30 x 40 x 2 cm

Hunter Smith, Productive Fantasy (2025), Oil on canvas, 29 x 40.5 cm

Regina McDonald, Self Portrait II (1999), Collagraph print, 35.5 x 30.5 cm

Luci Callipari-Marcuzzo, Invisible (2025), Household curtains, acrylic paint pen, thread, vintage cotton fabric, embroidery hoop, 38 x 12 cm

Kylie Fogarty, Back Rock (2011), Lightfast pigmented liquid ink and pigment pen on 300gsm Fine art CP paper, 34 x 3 x 49 cm

Beatrice Magalotti, Fragments (2024), Cotton material, machine & hand embroidery, screen printed words, 45 x 33 cm

Brigit Heller, Torn (2025), Brass, 30 x 40 x 1 cm

Linda Studena, Study: Waves (2023), Willow charcoal on plywood, 25 x 30 cm

Carmel Wallace, Venetian Optics (2019), Recycled optical lenses, antique Venetian mirror with Murano glass, antique silver cake stand, recycled imitation pearls, 30 x 30 x 30 cm

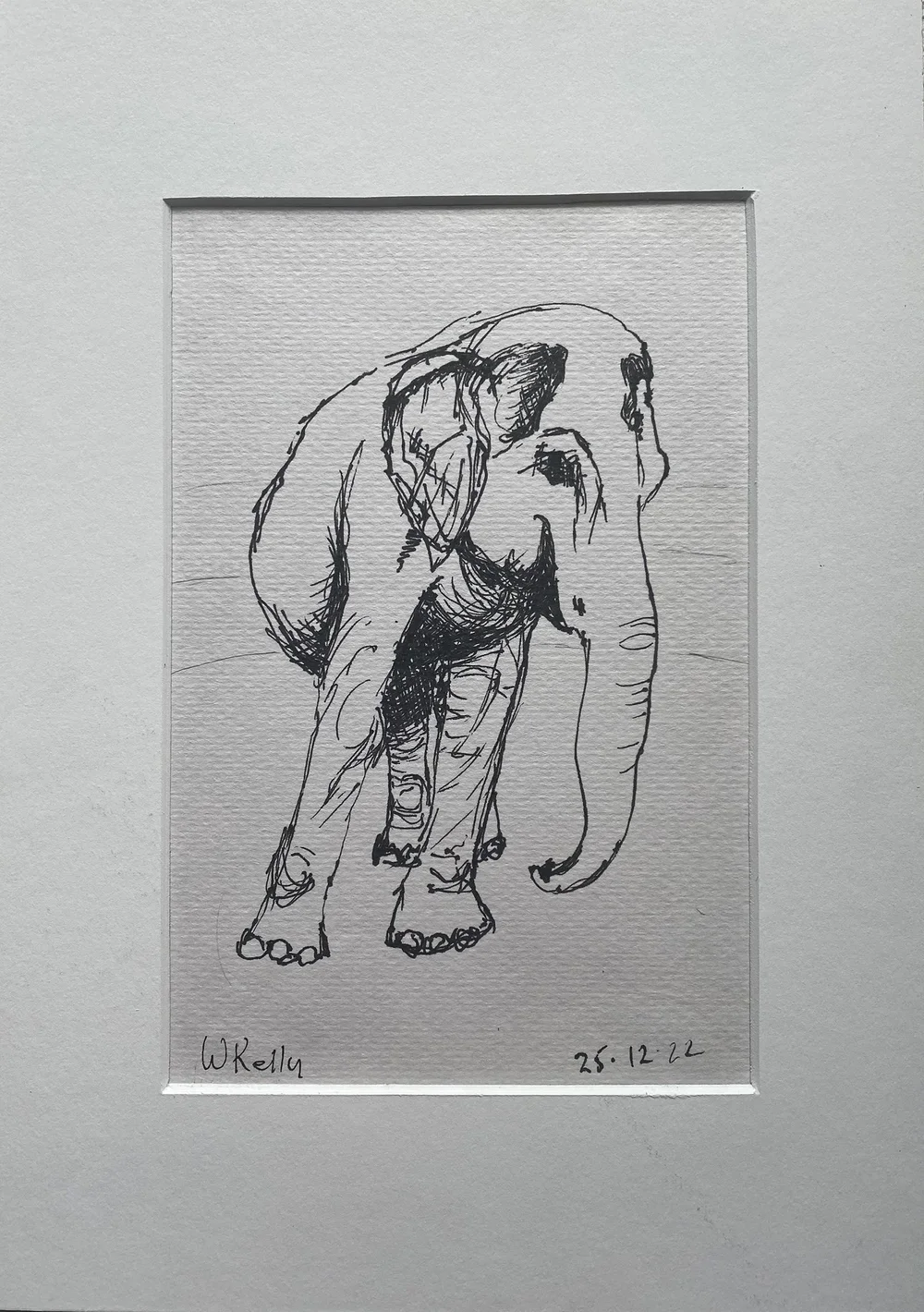

Wendy Kelly, Right Turn (2022), Felt nib pen on paper, 34.5 x 26 cm

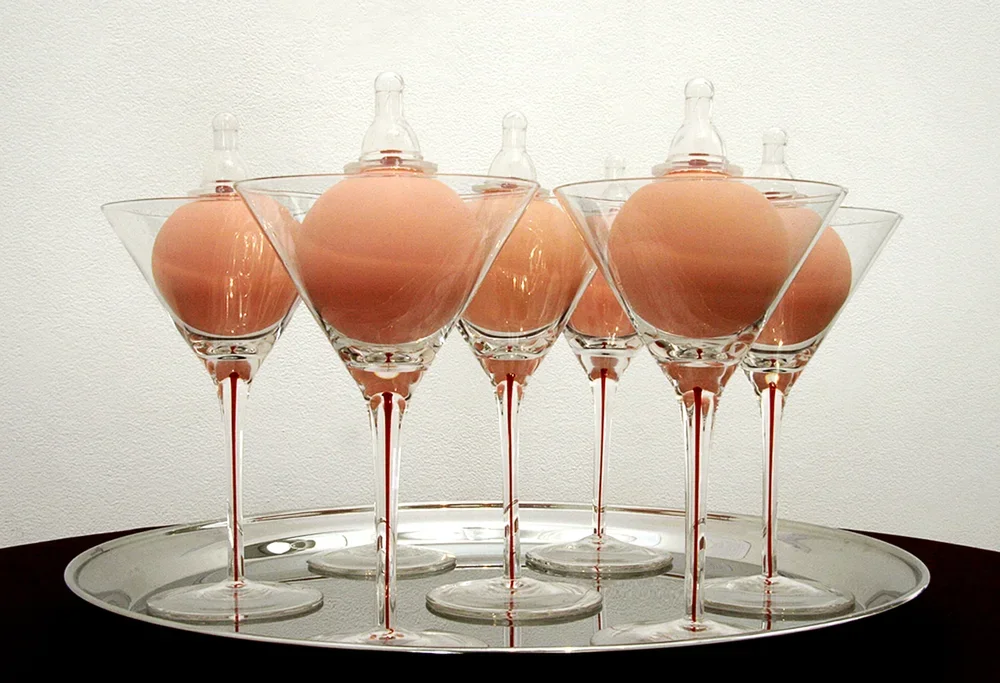

Pamela Kleemann-Passi, MarTiTis (2007), Archival digital print on Canson Rag Photographique Paper, 29.7 x 42 cm

Linda Judge, Nothing but Oranges (2024), Recycled plastic lids/wood, 30 x 30 x 40 cm

Jennifer Goodman, Lana 4 (2020), Tapestry (woollen thread, felt), 33 x 25.5 cm

Charlene Walker, Day on the bay (2024), Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 x 3.5 cm

Charlotte Clemens, Brunswick Street (2011), Monoprint, 40 x 32 x 2 cm

Katie Stackhouse, The Rapids (2023), Video and sound, 4 minutes duration

Fiorella Fabian, Swell (2022–25), MP4 video and sound, 5:11 min, 57 x 78 cm

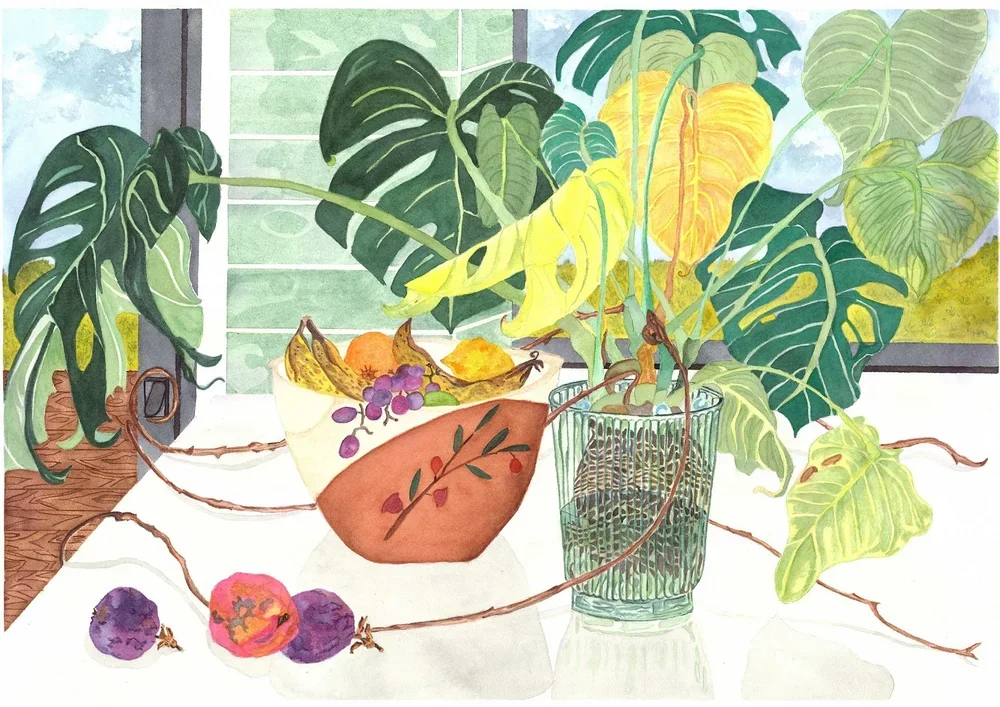

Rosalind Simonsen, Monstera Escape Plan (2025), Watercolour, 52 x 37 x 5.5 cm

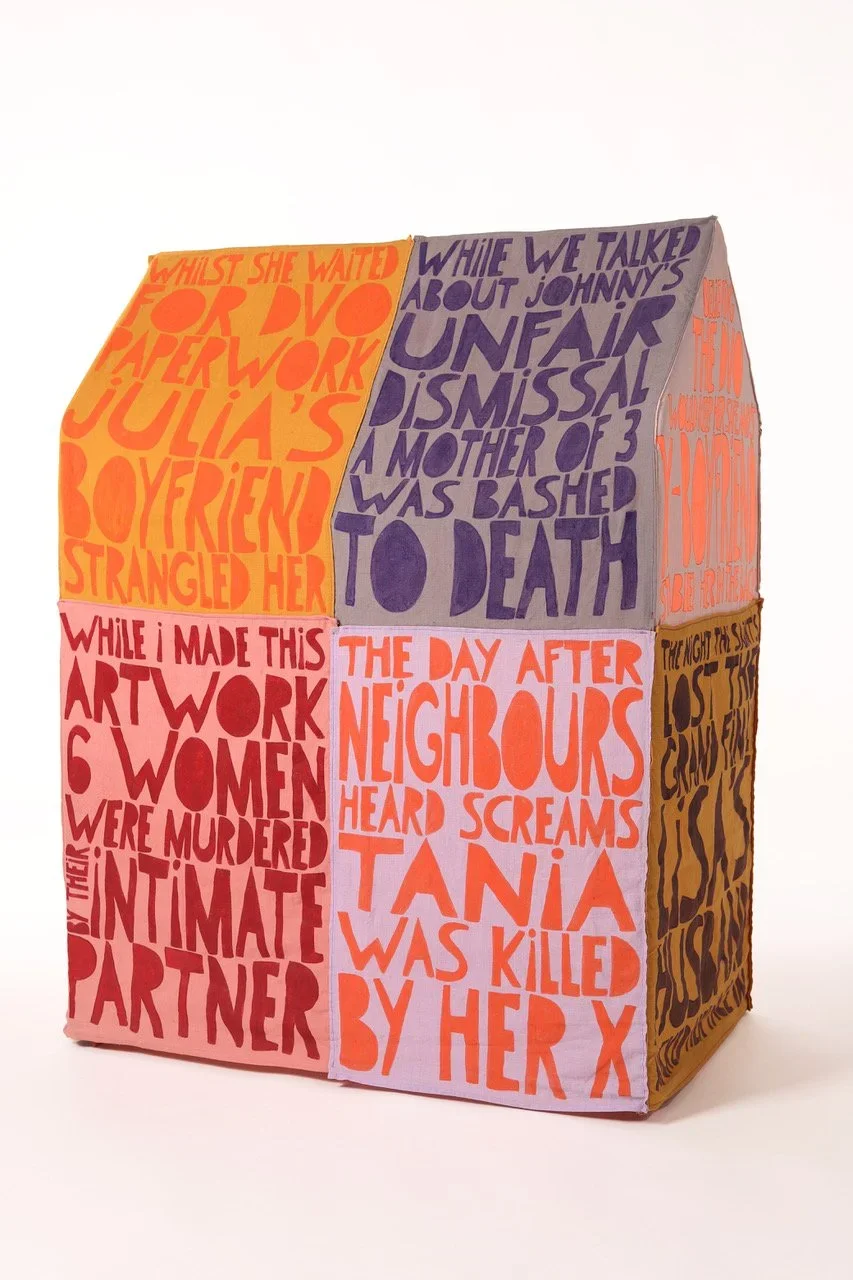

Ali Griffin, SAFE HOUSE (2023), Linen tea towels, fabric paint, wooden frame, 58 x 120 x 82 cm

Tania Lou Smith, Untitled (lawn blower) (2017), HD Video

-

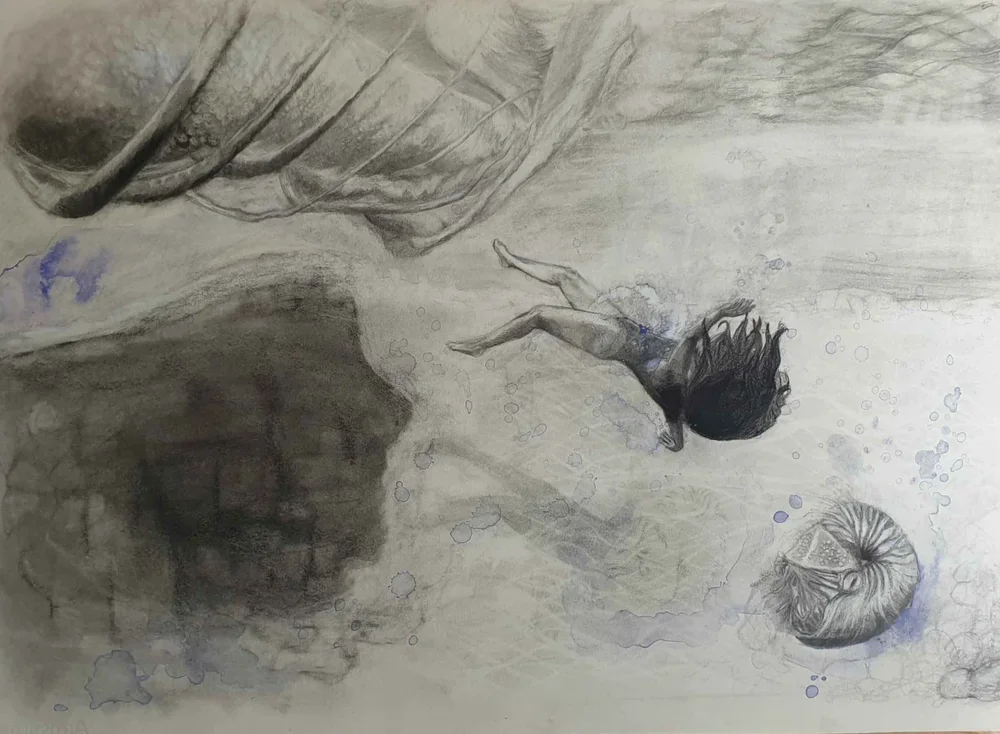

It’s 2012. There’s a small pit in my stomach, I’m not sure if it's grief or fear. My body remembers the cold, unforgiving bluestone floors of the Gaol cell. My bare legs exposed beneath the curtain of the artwork. I can’t see them. A feeling of disembodiment. Half my body is exposed to anyone visiting the Old Melbourne Gaol and the other obscured on the other side.

It’s now 2025.

I chose Vestige for the UNSEEN exhibition because 13 years ago the performance element of this artwork was abruptly halted. My safety had been compromised. My lecturer at the time decided to stop the performances.

I chose Vestige because it embodies the UNSEEN.

In the 1800s, conditions at the Old Melbourne Gaol were brutal. Cells were cramped and overcrowded—freezing in winter, a putrid hotbox in summer. The toilet bucket was emptied just once a week. Countless women and children, some as young as three, were locked up alongside violent men. It was institutional violence in its rawest form—everyone thrown in together: queer folk, disabled people, the elderly, immigrants, and First Nations people. Then, and even now, the system didn’t care who they were and the complexity of their experiences.

It’s jarring to think that the Old Melbourne Gaol, a place built to brutalise, has been repurposed for tourism. What was once a site of colonial incarceration and state-sanctioned violence is now branded as a space for cocktail parties, corporate functions, and even weddings. You can celebrate love, sip champagne, or pose for photos in the same cells where women, children, the poor, the mad, the disabled, the unwanted, the racialised were once locked away, many never to walk out again.

School groups wander through on excursions. Tourists line up for ghost tours and reenactments of Ned Kelly’s final moments. There’s even an “interactive Lock Up experience,” where guests can be mock-arrested, fingerprinted, and thrown into the City Watch House cells. It’s trauma turned theatre. State violence packaged as immersive entertainment.

Is it historical education? Or is it poor taste wrapped in heritage branding? These institutions weren’t just part of our history; they are the blueprint for the systems we’re still fighting to dismantle today. The same logics of harsh criminalisation, racial violence, and carceral control persist. The conditions may have changed, but the punishment remains, especially for First Nations people, for Black and Brown communities, and other marginalised folk.

I’ve been inside that space, not just as a visitor, but as an artist.

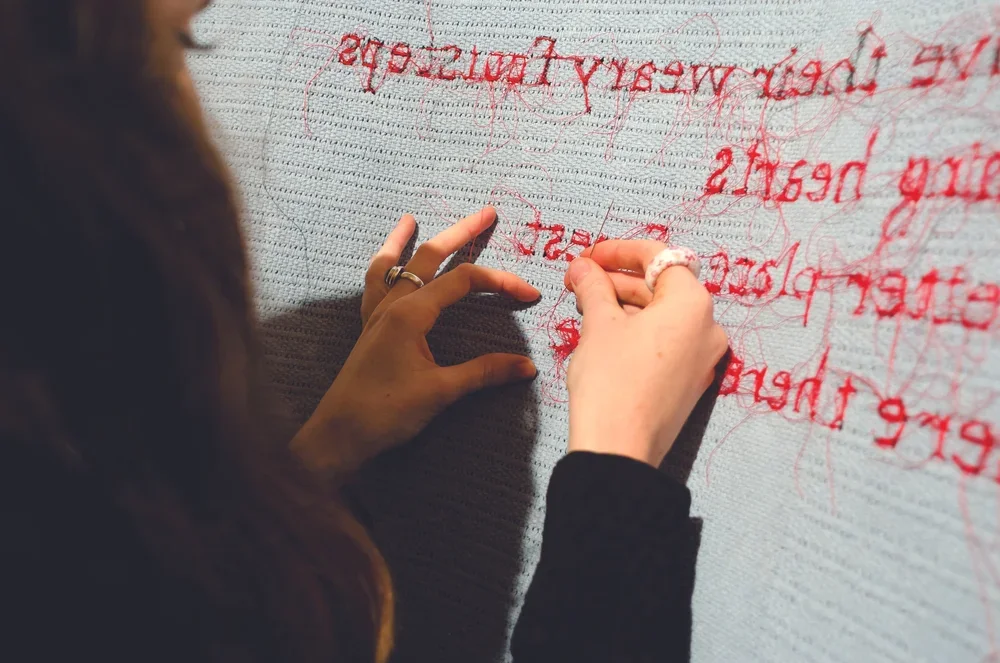

Back in 2012, I performed Vestige, inside one of those cells. The installation was intimate, durational. Over two weeks, I performed six times, two hours at a stretch. I sat behind a suspended, threadbare blanket with embedded fragments from the Register of Female Prisoners Penal and Gaol’s Branch 1857–1887, a ledger of names that remains one of the few traces of the women and children who were imprisoned there.

I sat for hours, silently stitching and unpicking holes, over the course of the performance, I stitched the quote: Heaven give their weary footsteps, their aching hearts, to a better place of rest, for here this is none (Robert Hughes). The actions were slow, repetitive, and deliberate, sometimes it felt pointless, boring and frustrating. A ritual for the lives of the women and children intertwined with a fate they can’t escape.

My upper body was hidden, only my bare legs visible through the gap beneath the fabric. I became a silhouette. An outline. Anonymous.

From that position—half visible, half erased, I heard everything. School kids, tourists, families, groups of curious onlookers would wander in. Some were quiet, respectful. Some tried to interpret the work aloud. But no one ever addressed me directly. The blanket became a wall, and I became a ghost, something to peer at, speculate over, consume.

Then came a group of young men. At first their comments were light, joking about how “spooky” it all was. But the mood turned quickly. The banter became violent. They egged each other on—“Rip down the blanket!” “Grab her by the legs!” I froze. Goosebumps rose on my skin, even though I was already cold from sitting for hours on that bluestone floor. I slowly withdrew my legs. No one intervened until, finally, a teacher or supervisor came in and led them away.

I had nowhere to go. No exit plan. I called a friend who was nearby to come and get me. Afterwards, my lecturer cancelled the remaining performances. He said he couldn’t guarantee my safety. I remember sitting with that, the cold still in my body, my mind spinning. I had entered the Gaol to create a work about grief, about institutional erasure and the violence of forgetting. And there I was, face-to-face with the very logics I was trying to expose.

But what would I know? My experience barely touches the surface of what it means to live through incarceration. What we need urgently are the hard conversations. The ones that make us uncomfortable. We need to step aside and listen. And more than that, we need to act all on the countless coronial inquests, and yes, on the findings of the 1987 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. It's all there. We've been told. The question is: when are we going to do something about it?

The Old Melbourne Gaol may be a heritage-listed tourist hot spot, but its foundations are still soaked in the logic of the colony. We can’t sip cocktails in these spaces and call it education when the violence is still ongoing, not when the same carceral logic continues to disappear people into prisons, especially First Nations people. What happens when sites of pain become playgrounds? When we package history for public consumption without confronting the systems that uphold it?

When I performed Vestige inside one of those cells, behind that threadbare blanket, part-visible, part-erased I was trying to make space for grief, for memory, for resistance. But what I encountered was a reminder of how little has changed. My body, partially exposed and anonymised, became a site of public property inviting curiosity, silence, even threat. The moment that performance ended prematurely, not by choice but by the threat of real violence, I was left thinking about how invisibility and vulnerability are so often entwined.

That reflection sits heavily as I now prepare to show Vestige again, this time as part of UNSEEN, an exhibition that brings together works by W.A.R. members that, until now, have had little or no public exposure. Each piece in the show holds a story that’s been hidden, overlooked, or erased, just like so many of the artists themselves. Together, these works refuse silence. They confront the historical underrepresentation of women in the arts and insist on visibility, recognition, and agency on our own terms.

Change moves at a glacial pace. Every day, all over the world, women and children are subjected to men’s violence.

Racism remains alive and seething in our communities, genocide live on our screens.

Imperialism, the long shadow of colonisation continues to wreak havoc on generations of First Nations people.

On the surface, it might look like some progress has been made. But scratch that surface and it’s mostly just fluff, a bit of icing. And when the ingredients of the cake come from colonisation and patriarchy, the taste is bitter. For those in control it’s familiar, comforting, even. That good ole’ dependable flavour of white privilege. A system built to punish poverty while upholding systemic racism, working exactly how it was planned.

In 2025, Vestige might just be a trace, a remnant, but it's also a protest. A collective of names remembered. A reclaiming of space and story. Because until we reckon with where we’ve come from and who’s still being left behind, no amount of historical rebranding will heal what the colony continues to harm.

-

I work with diverse media, but some of my work and modes of making are unseen. It isn’t possible to show all the work done. Only some make it to exhibitions. Some are recycled into later works, sold, dismantled or gifted. Most of my ephemeral, temporary light installations, videos and photographs have never been exhibited. Most work from residencies are only seen by the local people who live nearby.

I undertook a month-long residency in 2023 at AIRSpace, Oatlands, Tasmania. I spent most days exploring the town, countryside around the town, historic buildings and painting, while nights were spent outside the sandstone historical studio, gallery and accommodation house. I was setting up temporary light installations, videoing and photographing them. I was alone, and often windblown and skittish stumbling around in the dark.

One image of the installation in the front windows was printed in the local paper. The work exhibited in Unseen at ACU is Rear window, 2023 and is an example of these many thousands of photographs taken. Many move past documentation and become works unto themselves.

Here are a few other images from this residency.

While in lockdown I collected images of my artwork practice over the last five decades and compiled them into books. This visual archive provides further images of this residency.

Space Is Never Empty is a series of six books self-published through IngramSpark and available through most book outlets print on demand or ask your library to order it in. I have donated a series to the Women’s Art Register library.

They are also widely available as eBooks on devices and apps so the images of artwork can be seen larger on screens, in more vibrant colour.

-

There is mystery, effort, love and even anguish in the unseen. Deep empowering feminine instincts may even flourish in these nourishing spaces. That quiet solitary time brings new creations to life. Creativity is initially an unseen process; a spark is captured, it is explored and developed into something tangible. At that stage it may enter the public sphere or remain hidden.

Creativity is a gift, a joy that rivals any other pursuits. In those moments it feels like the heart and mind are functioning at capacity and in unison. I’ve always been grateful in those moments.

My process for creating new pieces is usually, inspiration, research, working with clay, colour matching and then bringing it all together with a little history. Jewellery has always been about symbolism and empowerment over the centuries, especially when women had little power over their own lives. Some of these symbols and talisman were on display, but others were hidden away in dangerous times. Having beliefs or thoughts that were not the majority had to go unseen. The desire to be ourselves shines brighter today, especially in the way we express ourselves through caring, conversation and art.

Circumstances are often changing in a women’s life; study, career, family, community and keeping a watchful eye on the world, to name a few. I hope newly crafted pieces will find their way to wherever they are meant to be, even if that means a few boxes stored away for a very long time or new collections online and in public spaces.

-

A most enjoyable residency at the Australian Tapestry Workshop in 2016 gave me the opportunity to explore and experiment with woollen thread and felt—a totally different medium to painting, which is the main form of my practice.

The needlepoint tapestry has proven to be a natural medium for me as my approach demands a similar obsessive perfectionism in each stitch as does each indiscernible brushstroke I apply to my canvas.

Colour is central to my practice. Making Lana 4 allowed me to enjoy the challenge of working with colour and tone using wool in placement of the paint I’m so familiar working with. Extending the colour palette to the frame has completed the picture.

It is rewarding to see that tapestry, historically viewed as a ‘women’s’ craft, is now considered to be a legitimate artistic method with many contemporary artists exploring this medium. I’m happy to have shared the experience.

-

Unlike traditional frames which often follow the fashion and style of the time of painting or are clumsily added at a later stage, my frames respond to the image or meaning of the image directly.

I am inspired by historic golden frames. Sometimes the image itself takes precedence and the frame plays with the elements of the reconstructed artwork. At other times it expands on the story itself.

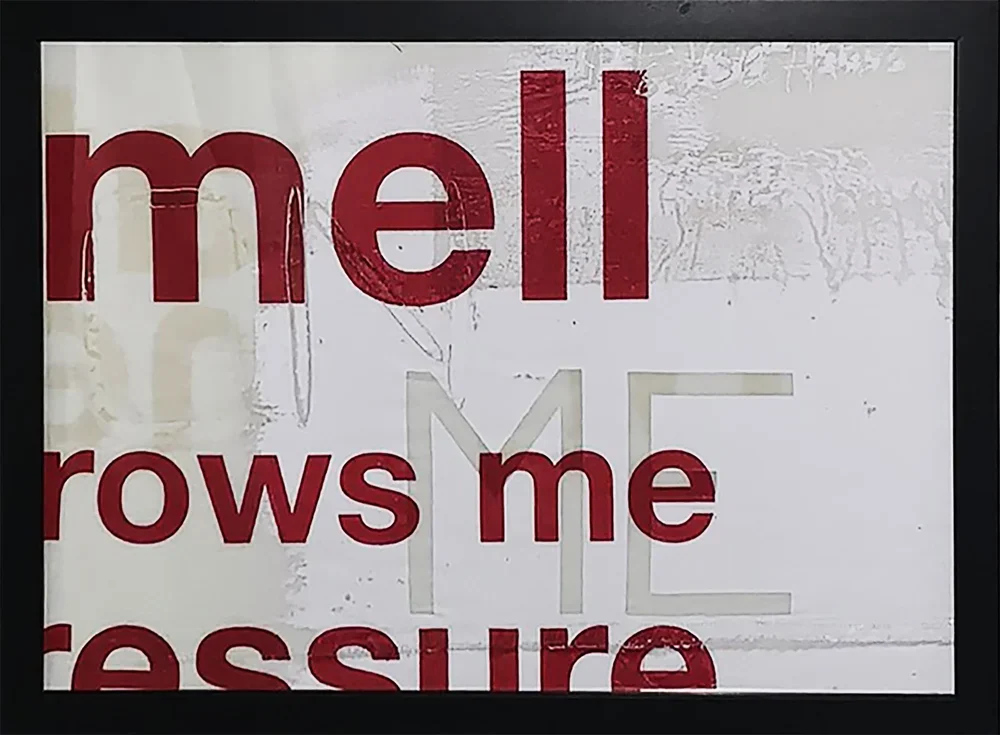

By first embroidering and then framing Maria Likarz’s Head of a Girl I am not simply seeking to re-frame our perception of the work but in a small way, I am asking the viewer to reconstruct their own understanding of the women who have persisted against the dominant male narrative. This is part of a larger body of work that honours women throughout history.

My interest in gilded frames started a long time ago.

I grew up surrounded by high mountains and baroque architecture. Initially I hated all those frilly golden churches till one day I entered a huge baroque church. Organ music was reverberating through the nave and aisles. Music of the 18th century. Suddenly I understood. The music, the architecture, the sculpture, the gold, the opulence … It all fitted together and made sense. This was the art of my mountains.

The use of embroidery is deliberate.

When I started making the frames I was not concerned about the images themselves. I chose an image because it spoke to me, because it meant something to me. Slowly the images became very specific, the frames were also adapted to the image and then the question arose about copyright. The natural step for me to take was embroidery. Photoshop, collage or any other form of alteration was too new. Embroidery was the link to the distant past and to the beginnings of the movement towards equality.

“Some of their earliest products were displayed at the NUWSS procession of June 1908 during which 10,000 people marched on parliament to demonstrate their determination for the vote to the newly instated prime minister, Herbert Asquith. The Artists’ Suffrage League designed and made eighty embroidered banners for the march, which constituted the ‘most beautiful art exhibition of the year’. The choice of medium was no accident. Political marches were antithetical to conventional standards and expectations of female behaviour.” Maria Quirk in NGV Magazine, July/August 2019.

The choice of medium was no accident for me either. More than one hundred years later, embroidery might not be the typical craft of the 21st century woman, but it links us to those who made it possible for women (in some parts of the world) to vote and be part of political life now.

It also reminds us that we still have not reached our goal of equality for all minority groups, including the largest “minority” group in the world, Women.

If the frame is a “physical division between artwork and architecture, image and object” my knitted frames try to blur that. Not only does the technique elevate them to the artwork itself but they also comment on the embroidered image itself. We are left exposed to the question, where is the boundary between art and craft.

By reworking images, using domestic/feminine techniques of knitting, crocheting and embroidery attention is drawn to issues of present day importance, particularly the exclusion of women in numerous facets of everyday life.

Additional information

The Women's Art Register 50th Anniversary program is supported by the City of Yarra.